Slave Ships on the Delaware

The Waterborne Slave Trade of 18th-Century Philadelphia and Camden, N.J.

Produced in 2009, this seven-minute video was the first to detail how local officials, historians and cultural leaders had long failed to acknowledge or erect historical markers for Camden’s slave-trading history. During the eight years between 2009 and 2017, this video was viewed more than 50,000 times on multiple Youtube sites and other online video distribution outlets. Finally in 2017, the city, its local and regional cultural institutions and business leaders, erected markers detailing Camden’s former role as the hub of the region’s trade in enslaved africans.

CAMDEN, N.J. — The story of slavery in the northern states has long been a low-key subject for those who have written the country’s history books. In recent years, however, northern slavery has gained a good deal of traction as a topic of public interest, particularly in the area of Philadelphia and adjacent southern New Jersey.

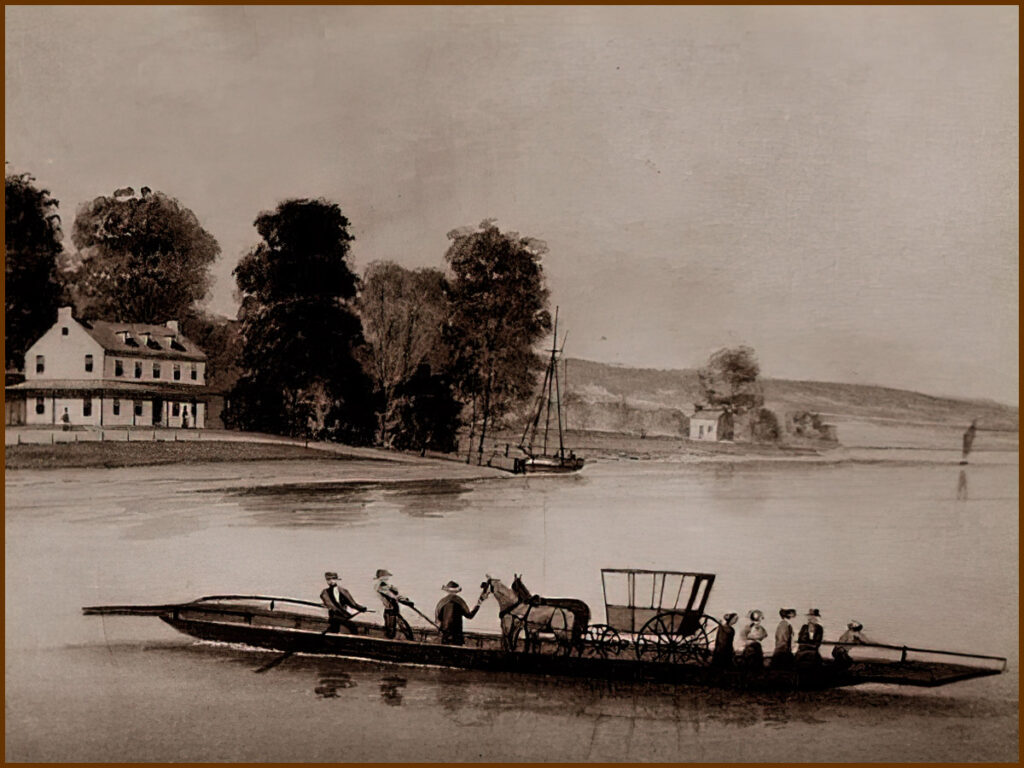

George Washington’s Slaves

George Washington used 316 slaves to work the Virginia plantation lands that were the basis of his personal wealth. This portrait shows Washington being attended by one of his slaves as he traveled along an area of the Hudson River. Larger image.

In Philadelphia, a years-long controversy raged over the archaeological excavation of the slave quarters at George Washington’s Philadelphia White House. The President’s House historic site, with a memorial to its slave laborers, finally opened in December of 2010.

The original building on Market Street was the official home of the first President of the United States from 1790 to 1797.

George and Martha Washington used more than 300 slaves to operate their Mount Vernon estate and plantation in Virginia. And when he was elected the country’s first President, Washington brought nine of those slaves to his President’s House in Philadelphia.

Demolished long ago, it was partially recreated as part of the latest upgrade of the Liberty Bell site in Independence National Historic Park. The lengthy debate about how to best commemorate the enslaved Africans who served in that first White House also sensitized the public to the larger picture of 18th-century slavery in Philadelphia and Camden directly across the Delaware River.

Delaware Valley Slavery

In fact, there was nothing unique about Washington’s use of slaves in his Philadelphia White House. The Delaware Valley regions of southeastern Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey were societies heavily dependent on slaves in the late 17th and 18th centuries. Both areas were home to plantation businesses that took advantage of the region’s fertile soil and temperate climate. These crop and livestock operations used enslaved Africans and indentured Europeans as a labor force.

But what does surprise many is that Quakers played such a large role in establishing and maintaining this slave-powered local economy. This is the same Quaker society that would later be best remembered for leading the movement to abolish slavery. But during their first century and a half in the region, many Quaker farmers and tradesmen built their family fortunes, in part, on slave labor.

In the late 1600s and throughout the 1700s, many of Delaware Valley’s founding Quaker families owned slaves. That includes clans like the Coopers, Mickles, Kaighns and Hinchmans who are still memorialized in street names and other institution names throughout what is now Camden County.

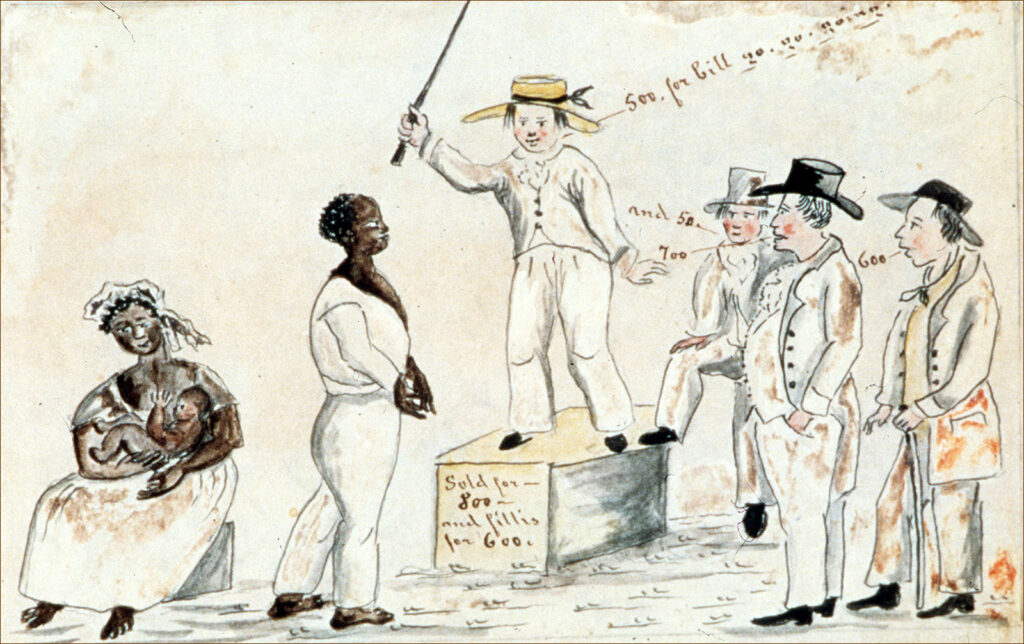

Camden’s Quaker Slave Traders

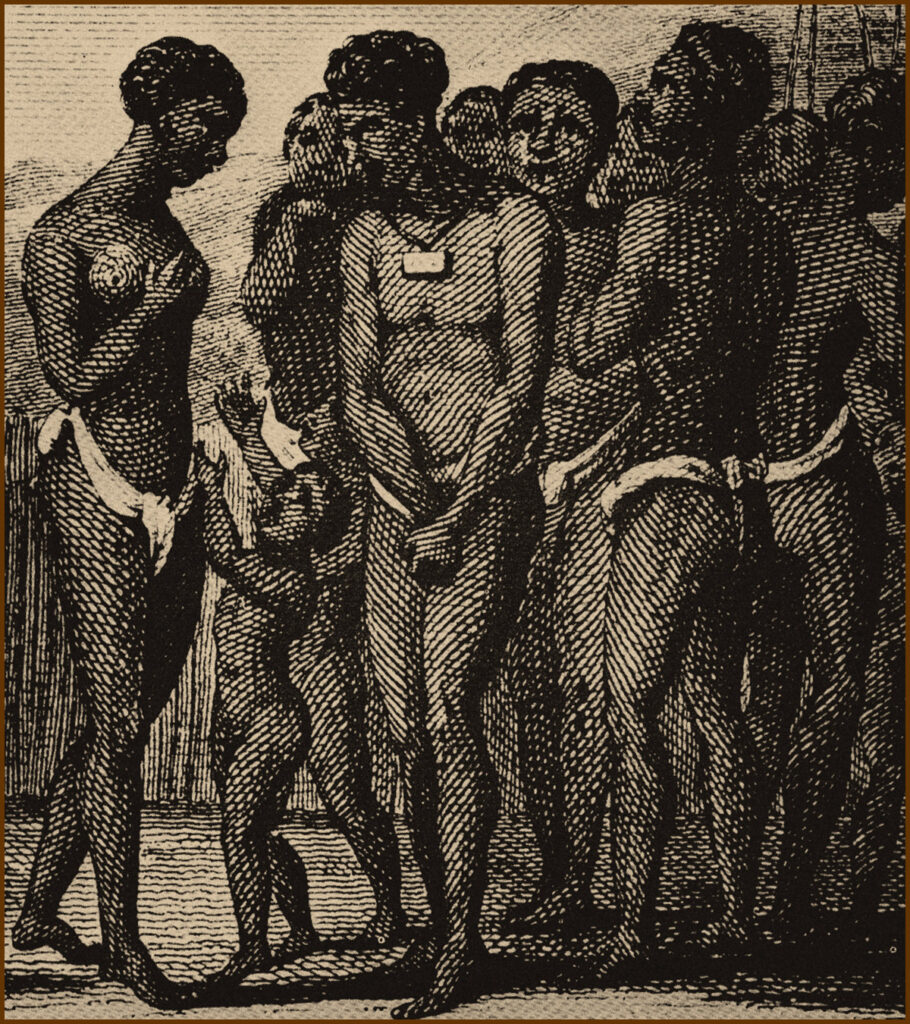

In addition, the business of importing and trading in slaves was dominated by Quakers operating out of the Camden ferry landings that doubled as slave auction sites. They were cargo landing points for ships sailing directly from Africa. These included Benjamin Cooper’s Ferry, Daniel Cooper’s Ferry, Samual Cooper’s Ferry and Robert’s Ferry. The ferry landing auctions serviced a market of slave buyers from across southern New Jersey as well as the Philadelphia region.

Meanwhile, the area’s 18th-century newspapers served as major tools of this slave trade — providing that era’s primary means of announcing the latest slave ship arrivals. Those vessels anchored off the Camden side of the river and used newspaper ads to invite slave buyers to Camden’s ferry sites to view the African men, women and children then currently on sale.

Local Newspaper Slave Ads

Those same local newspapers’ slave advertisements now provide a vivid sense of that local slave trade. Such slave ads heralded arriving slave ships, described individuals and groups of Africans, offered rewards for the capture of escaped slaves and were used to conduct a second-tier business dealing in the re-sale of locally-owned slaves.

Still surviving in Camden is Pomona Hall, the 18th century mansion of Marmaduke Cooper who owned at least 14 enslaved Africans. The building, now owned and operated by the Camden County Historical Society, is restored to what it would have looked like in the 1780s when it was the “big” house of a Cooper’s 400 acre plantation. The hundred-year old Historical Society began to tell the story of local slavery 22 years ago and continues to do so today.